How do you cope with your son’s suicide?

Sam Harrington-Lowe speaks to Julie Burchill about the suicide of her beloved son Jack Landesman (above), and how attitudes to mental health have changed since 2015

My first ever job, when I was about 15, was at a Happy Eater in Hooley; long gone now, morphed into a Starbucks or something. And close to the restaurant, nestled at the top of long driveways, hidden out of sight, was not one but two mental health institutions – in those days, called asylums. We were fascinated by them.

Both the hospitals – Netherne Hospital and Cane Hill Hospital – were a source of legend and Lynchian allure to us locals. I can remember a night when drunk teenage me – together with more drunk teenage cohorts – decided we should sneak a look through the windows at Cane Hill; an imposing Victorian asylum steeped in legend, where screaming electric shock treatments and padded cells were alleged to be de rigeur.

The madhouse

Venturing up the hill we were whispering and giggling, hoping but also afraid that we might see crazies through the barred windows; screaming or gagged, tethered to their beds with thick leather restraints or thrashing about in straightjackets. We knew there were patients who had been incarcerated for years, lost in time, like the Queen’s mad cousins in a nearby Earlswood sanitorium, and we wanted to see them.

We imagined tortured souls in shackles and long nightgowns, undergoing hideous sadistic treatments as they were forced to clamp down on rubber wedges, lest they bite off their own tongues. We’d seen One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, right?

We were disappointed, but we were chased away by a security guard, which added to our own mythology. What were they hiding?

Care in the community

The truth is, not a lot. By the late 1980s (this was about 1986) the number of patients had greatly declined at Cane Hill – and in all asylums – due to the recommendations of the Mental Health Act (1983) and its emphasis on care in the community.

Cane Hill Hospital

Cane Hill (above) is now a Barratt Homes development, and Netherne Hospital is a development that includes 440 houses, a nursing home, a business centre, a shop, and a public house. The inmates – sorry, patients – long released into the bosom of non-institutional love are long gone, their restraints replaced by medication and home visits. But the lingering legends of old endure.

The building of Cane Hill was commissioned by a governing body called The Lunacy Commission, established by the Madhouses Act 1882. It all sounds a bit Monty Python, doesn’t it, and seems extraordinary to us modern folk that we should apply such terms to the mentally ill these days. How far we’ve come since then.

But how far exactly have we come in 30-odd years?

In the eighties, mental health still carried with it a huge stigma. People whispered about others having ‘nervous breakdowns’ and losing one’s mind; of ‘hearing voices’. The only time it was acceptable to be mad was if it was drug-induced, a la Withnail, or Syd Barrett.

Pretending that mental health isn’t a serious issue just isn’t acceptable anymore

These days it feels like unless you have some kind of mental health issue, or perhaps you’re not neurodiverse, or suffering PTSD, or have long-carried trauma… well, you’re the exception, not the rule.

It’s arguably more productive and healthy to explore this. Pretending that mental health isn’t a serious issue just isn’t acceptable anymore and I for one am pleased we are more open about treating this.

But more importantly, although we are indeed more open about discussing our mental health issues, we’ve still got a long way to go when it comes to knowing how to cope, or deal with them. It’s a bit like finding you’re actually not mad but autistic. So that’s great, but what now?

Suicide is still a real thing

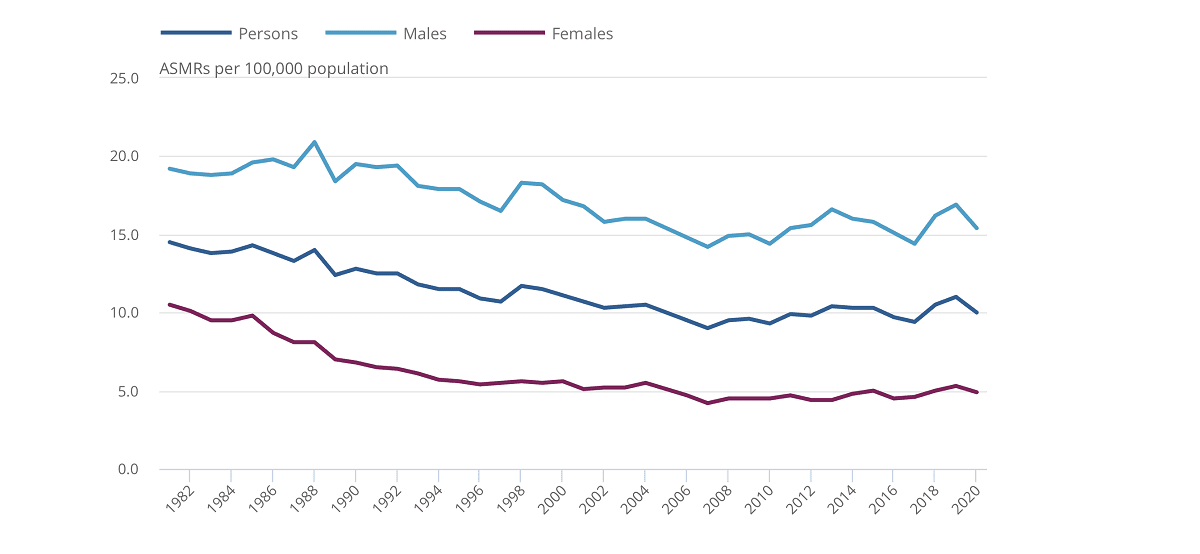

Suicide rates have fallen since Covid kicked in – in fact, suicide rates have fallen pretty much consistently since 1981. But regardless, the percentage of deaths by suicide by men sits at around the 75% mark, and historically always has.

Julie Burchill photo: Sam H-L

Julie Burchill lost her son to suicide. I say ‘lost him to suicide’ but he was lost, long before that. Years of mental struggle finally culminated in what can – for him – only be seen as the relief of death. He’d been ill for years, stuck in a tortured cycle of medication and treatment, recovery and remission, until one day he finally got his wish, and died. It wasn’t entirely unexpected. So how do you cope with a son’s suicide?

“I was in Crete, having a lovely time with my husband,” remembers Julie. “We went back to the room after lunch and I opened my emails – there was one from a wonderful broad called Tessa Mayes who’d been helping Jack for the past year (to my shame, I hadn’t seen him since last summer) saying JACK URGENT CALL ME. I said immediately to my husband, ‘Jack’s dead.’

“I had been expecting it for years.”

The cost to carers

Anyone who has spent time caring for someone with mental illness will recognise how complex it is. There are no easy answers; for some, the path becomes easier, maybe they get fixed. For others, it doesn’t happen. Whatever the deal, it ultimately places huge pressure on those who are close.

In the old days, you got labelled a schizophrenic, an addict, a manic depressive, traumatised… These days the lines are often more blurred, and we’re learning all the time about the complexities. We try not to pigeonhole. But what makes one person recover, and another remain ill in perpetuity isn’t easily definable. One can be in a good place, a happy place, and still be steeped in torture.

“Some people can be fixed, some cannot. Jack first attempted suicide when it was the best his adult life had ever been, but he still wanted to die.”

Julie’s son Jack is a prime example. “Some people can be fixed, some cannot. Jack first attempted suicide when he was living with a lovely girl – a nurse! – whom he adored. And earning a living teaching guitar. It was the best his adult life had ever been, but he still wanted to die.”

I wondered whether he’d always been ill, or what first flagged it up. “He was cutting himself, had bulimia, was isolated… endless dope-smoking, you name it. He flunked out of university twice and BIMM once, two weeks before graduation. From the age of 19 till he died at 29, he was completely self-destructive.”

As with many cases, it isn’t so much that Jack wanted to die – he just didn’t enjoy living. There is poetry in death, for sure, as Plath and many others will attest to. But it’s the living bit that we need to deal with, and deal with better.

Sometimes you have to let people go

Helping people who are ill, whether they’re depressed or riddled with cancer, wreaks its own damage on the carer; something Julie is keen to hammer home. “Help all you can, but put on your own oxygen mask first, as they say on the plane. Do not let the illness of your loved one destroy you.”

In the meeting preamble of Al-Anon – the fellowship for the friends and family of alcoholics and addicts – one of the phrases used addresses this, suggesting that the key is finding “…solutions that lead to serenity. So much depends on our own attitudes, and as we learn to place our problem in its true perspective, we find it loses its power to dominate our thoughts and our lives.”

Helping people who are ill, whether they’re depressed or riddled with cancer, wreaks its own damage on the carer

So if placing the desire to die in its true perspective is allowing them to fulfil that wish, then letting them get on with it is something Julie advocates. “If they have asked, and proved, time and time again, that they want to go, LET THEM GO. If you love them, let them go – no matter what pain you will have to suffer when they do.”

It’s an extraordinary level of acceptance, to embrace such a position. Not everyone wants to die, but hey, maybe we could all just be a bit less judgemental? A bit more understanding? What’s really key here is the overwhelming evidence that carers need support just as much as those who are ill. It’s not an easy ride.

Finding ways to cope with grief

So how do you actually even start learning to cope with your son’s suicide? Julie is working through her own pain by volunteering at a MIND shop – where she’s been volunteering for six years, since Jack died.

MIND is a national charity that provides “…advice and support to empower anyone experiencing a mental health problem. We campaign to improve services, raise awareness and promote understanding.”

What does Julie do there? “I like to do hands-on, menial things, as I think and write so much. I got to love steaming clothes when I was at the Martlets (another local charity), so that’s what do at MIND.” And how can you help? As Julie says, if you want to help, “TALK, TALK, TALK about it! GIVE MONEY! VOLUNTEER!”

Helping other people is good for the soul. Faith has also helped Julie to deal with the loss of her boy; “Faith in the Lord, and a wonderful husband,” she says. She believes that he’s at peace now.

“He was a good boy, a very good boy, till the sickness devoured him. I believe he is himself again, in Heaven.”

HELP AND SUPPORT

MIND is a national mental health charity – great for supporting you can find them at: www.mindcharity.co.uk

Suicide in men… male suicides account for 78% of all suicides and are the single biggest cause of death in men aged 20 – 45 in the UK. For help and advice, please contact www.thecalmzone.net

Always there for you, any hour of the day or night – Samaritans www.samaritans.org

Sam is Silver’s founder and editor-in-chief. She’s largely responsible for organising all the things, but still finds time to do the odd bit of writing. Not enough though. Send help.

Leave a comment