Polari, Britain’s secret gay language and its influence today

Author Paul Burston reflects on how Polari, a coded language with a colourful history, is still having an influence on LGBTQ culture today

What is Polari? Sometimes spelled ‘palare’ from the Italian ‘to talk’, it’s a form of slang most commonly associated with gay men, used more widely during the days when male homosexuality was against the law.

The language itself has diverse origins – a combination of Italian and Romantic roots, Romany, backslang (saying things backwards), Yiddish, Cockney, and other street and sailor slang, mostly from London.

The point of Polari was, largely, to avoid the law knowing what the hell you were talking about

The point of Polari was, largely, to avoid the law knowing what the hell you were talking about or getting up to. And so to keep ahead of intelligence, the language was a constantly evolving thing, staying one step ahead. Many of the words have made their way into common parlance.

In 2021, Polari lives on as the inspiration for literary events and awards where the focus is very much on inclusivity. Polari is still relevant and part of our history. Although gay rights have come far in the UK, there is still a way to go.

The origins of Polari

The origins are complex. At various times, circus folk, sailors, Romany gypsies and other social outsiders spoke Polari, but it’s most commonly associated with gay men. In the 1960s, it was popularised by Kenneth Williams and Hugh Paddick as camp comedy couple Julian and Sandy on the BBC radio show Round the Horne. Their conversation was laced with sexual innuendo and made regular use of Polari.

They used slang like ‘bona lallies’, which means ‘nice legs’, and ‘dolly eke’, which means ‘handsome face’, in a knowing way that many gay listeners of the time would have recognised.

Other cultural icons using Polari

When David Bowie launched his Ziggy Stardust character and album in 1972, he gave a famous interview to Melody Maker. He camped it up outrageously, claimed he was gay and spoke in Polari to prove his queer credentials; despite being married with a child. His final album Blackstar also contains elements of Polari on the track Girl Loves Me.

Polari was vital to the gay community until very recently

Polari is sometimes referred to as ‘the lost language of gay men’. It was most popular after WWII and before the 1967 Sexual Offences Act, when male homosexuality was against the law.

You could be fired from your job or refused accommodation simply for being gay.

Thousands of gay and bisexual men were imprisoned for consensual sex acts. Men used Polari as a coded way of communicating with each other at a time when being openly homosexual carried the risk of arrest.

There are words that have made it into common parlance, used to this day. Like ‘naff’, which originally meant ‘straight’ or ‘Not Available For Fucking’.

The 1967 Sexual Offences Act was a watershed moment, but…

Contrary to popular belief, the act didn’t actually make gay sex legal. It only decriminalised it under certain circumstances. The age of consent for gay men was set at 21, compared to 16 for heterosexuals. Homosexual acts were tolerated, providing they took place in private and no more than two people were present.

The freedom that straight people take for granted weren’t afforded to us. If a nosy neighbour spotted two men kissing – inside their own home – and reported them to the police, they could be charged with a public disorder offence. You could be fired from your job or refused accommodation simply for being gay.

It’s worth remembering that this remained the case until a mere 20 years ago. Public displays of affection could, and often did, still lead to arrest.

Astonishingly, the specifically gay crime of ‘gross indecency’, for which Oscar Wilde was imprisoned more than a century ago, remained in law until as recently as 2003. These days we have an equal age of consent, partnership rights and employment rights. All of these things were unthinkable back in 1967.

It is easier to be a gay man in the UK today, but again…

A lot might have changed since 1967, but homophobia hasn’t gone away. It still isn’t safe to walk the streets holding your partner’s hand, or look a certain way. There’s always an element of risk involved.

In the last year there’ve been violent homophobic attacks on gay men in Birmingham, Edinburgh, Manchester, Liverpool, and London. A friend of mine was attacked in Brighton. I’ve been assaulted many times in London. It’s easier now than it used to be but it’s still far from ideal.

It’s always been harder for lesbians

They weren’t criminalised the way gay men were, but they did face persecution and were often invisible in a way gay men weren’t. And the notorious Section 28 affected lesbians just as much as gay men, by describing relationships as ‘pretended family relationships’ and making any discussion of our lives during sex education lessons unlawful.

…it’s important for gay men to support our lesbian sisters, just as they supported us during the AIDS crisis

Many young people who grew up lesbian or gay were taught that it was shameful.

Lesbians were at the forefront of the fight against Section 28 and heavily involved in AIDS activism – a fact often glossed over or forgotten. As women, lesbians are doubly oppressed as they also don’t enjoy male privilege. And misogyny and sexism aren’t the exclusive preserve of straight men; some gay men can be just as bad.

These days, there are very few lesbian-only social spaces left. And sadly disputes between some sections of the lesbian community and some trans activists have led to a lot of animosity and division.

I fully support trans rights. And I also think it’s important for gay men to support our lesbian sisters, just as they supported us during the AIDS crisis. In fact, I consider it my moral duty.

I celebrate Polari to keep history alive

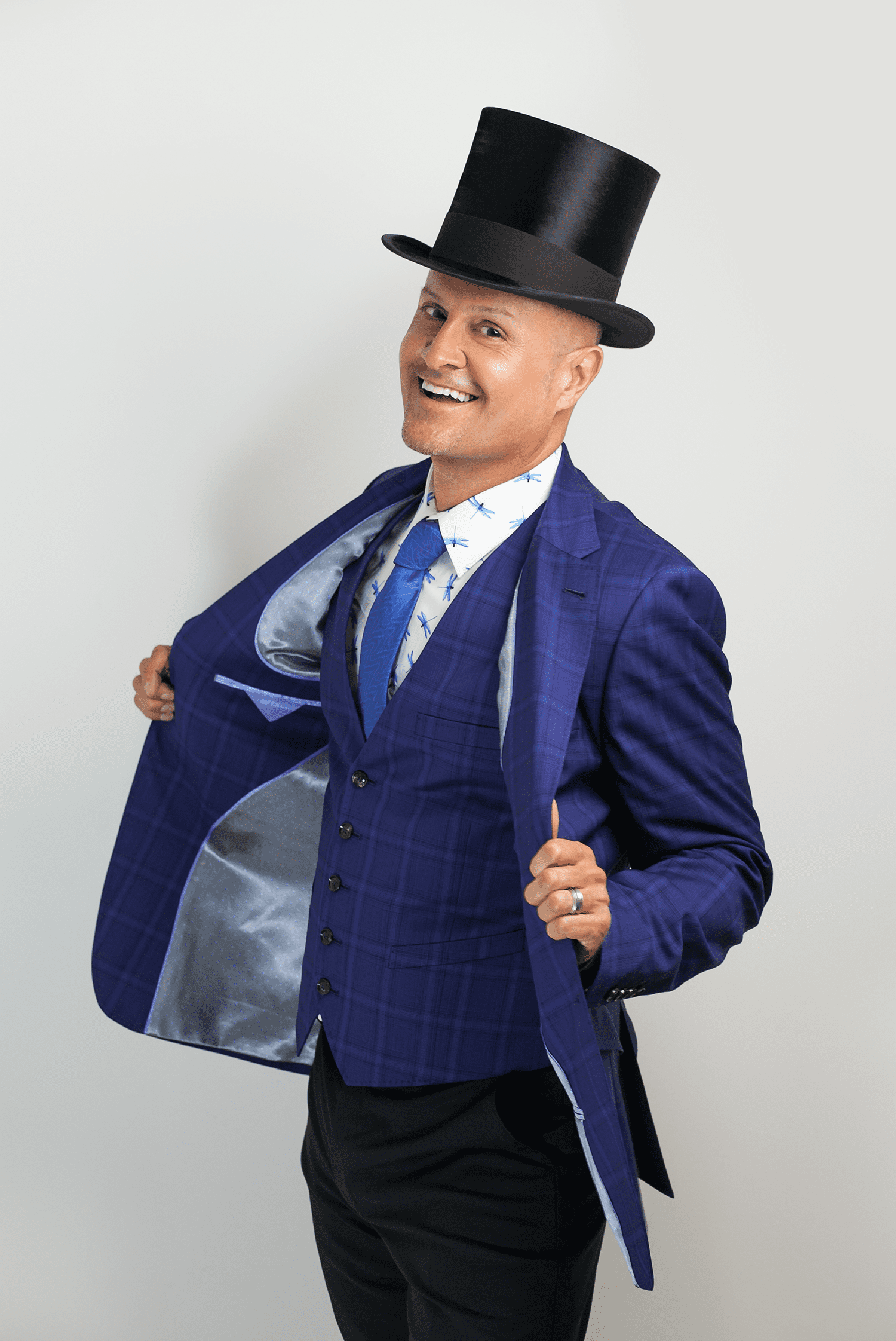

I created a live event, a literary salon, to help celebrate and explore the language. Polari is a live showcase for LGBTQ literary talent. It started in 2007 in Soho, London, and grew quickly. We’re currently based at the Southbank Centre, and tour regularly, thanks to Arts Council funding.

I think of it as a cabaret or variety show in which all the acts are writers of one kind or another – authors, poets, spoken word performers. It’s very diverse and very inclusive. Everyone is welcome, regardless of gender or sexuality. And we run two book prizes, for debut and established LGBTQ writers; it’s the only such prize in the UK. And we’ve been touring the UK, as we have every year since 2014.

For more information about Polari events: www.polarisalon.com

Polari words still in common parlance…

Bevvy: drink

Bijou: small

Butch: masculine; masculine lesbian

Camp: effeminate (origin: kamp = known as male prostitute)

Carsey: toilet, also spelt khazi

Crimper: hairdresser

Dish: an attractive male; buttocks

Dizzy: scatterbrained

Drag: clothes, especially women’s clothes

Fruit: queen

Mince: walk (affectedly)

Naff: bad, drab

Scarper: to run off

Scotch: leg (scotch peg)

Slap: makeup

Trade: sex

Troll: to walk about (especially looking for trade)

Author of six novels including The Closer I Get. Memoir We Can Be Heroes published June 2023. Founder of Polari literary salon and the Polari Book Prize for LGBTQ+ writing. Born in York, raised in Wales, now based in London and Hastings.

Leave a comment