Darkness falls across the land – and Nick Lezard is close at hand…

|

Listen to this article

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

As the wind howls in the darkness, and the trees scrape your windows, invisible fingers tapping, here’s Lezard’s guide to ghostly ghouls and scary stories…

There is a sadness, as well as a terror, about ghost stories: we may not want to be haunted, but we may want to haunt. Is an unappeased afterlife better than total annihilation?

Haunting a draughty castle with your head stuck under your arm may not sound like much fun, but it beats non-existence (for the non-Buddhist among you) or Hell (for the Catholic among you).

Ghost stories are best enjoyed at the liminal times of year: where autumn slips into winter; when the dark starts to last longer than the light; when the portal between the living and the dead worlds flickers into existence.

The most anarchic of customs occur around this time, the other time being April 30th, or Walpurgisnacht, when a similar inversion tales place. The ghosts seek closure, or vengeance, or just recognition. Don’t we all?

Be careful what you wish for

As a child, and I cannot be alone in this, I both craved to see a ghost and craved not to see one. Scooby-Doo cartoons taught us that they did not exist, but that the fear of them was powerful. Ghosts now are more of a metaphor than an actual fear; like quicksand.

The great-grandfather of Scooby-Doo, of course, is The Hound of the Baskervilles, in which the spectral hound is – spoiler alert – just a bloody big dog with luminous paint all over it. It’s the first modern anti-ghost story, and I like to think that Scooby himself is an ironic nod to Conan Doyle’s creation.

But we still like being scared by them, and this is the time of year to do it, when darkness falls. The most famous ghost story of all was composed during the particularly miserable summer of 1816, “the year without a summer”. Mary Shelley, staying with Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley at the Villa Diodati in Switzerland, came up with a monster.

Frankenstein and other classics

Frankenstein’s monster

Frankenstein not a ghost story? Well, it may not be a conventional ghost story, but a ghost story was what Byron had asked everyone to come up with. And it is, after all, about a kind of survival of life after death. Not to mention that its very composition conforms to the classic way such stories continue to be told, right up to the days of The Simpsons: around a fire, and extemporised.

There had been ghost stories before: the so-called Gothic novels of the mid to late 18th Century had plenty of ghosts, but they are of debatable quality, i.e. I think they’re rubbish.

You could argue that Hamlet is a kind of ghost story, and indeed some of the elements of all the best ghost stories are contained in it; similarly Macbeth, with Banquo’s ghost scaring the bejesus out of the eponymous antihero. All children, in the days when they were obliged to read these plays, considered the bits with ghosts in them (or witches) to be far and away the best bits. (The other good bits were when people were killed.)

Henry Fuseli – Macbeth, Banquo and the Witches 1793-94. Petworth House collection

Are the parts of The Odyssey set in the Underworld a ghost story? Is Dante’s Inferno kind of a collection of ghost stories? Not really, even if they deal with the shades of the dead; but they do provide a kind of authority or reference point for the more contemporary ghost story.

Proper ghostly horror

But the best ghost stories, of the kind that we now understand as ghost stories, came about in the lateish 19th and early 20th centuries, with the big literary gun among these being Henry James, whose stories “The Jolly Corner” and The Turn of the Screw are still – especially the latter – capable of giving even the jaded modern reader a frisson. Not to mention the fact that students groaning under the wight of James’s epic sentences in his more ‘serious’ works have seized with relief the relative simplicity of his narrative here.

In The Turn of the Screw we have lots of candles being mysteriously snuffed out, and apparitions at windows. And the notion, which had escaped people at the time, that everything was a figment of the governess’s imagination, gives things a surprisingly modern twist.

Before then we had, of course, Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. And even though we have Marley’s ghost clanking its chains, I am not sure it is the kind of ghost story we are after. It is rather didactic and has a soppy ending. I do not think ghost stories should have soppy endings, or even happy ones.

Much more satisfactory is Dickens’s own “The Signal-Man”, whose appearance portends some terrible railway accident. The reason this is such a good story is that Dickens had skin in the game, so to speak. The year before he had been in the famous Staplehurst rail crash, and had been severely rattled, both literally and metaphorically, by it.

Fear of the unknown

But the really big beast in the ghost story canon has to be MR James (no relation to Henry). Here is the genuinely spooky stuff: there are grown men I know, and I am one of them, who come over all queer, in the old-fashioned sense of the term, when they hear or read the very name of his most famous ghost story, “Oh Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad”.

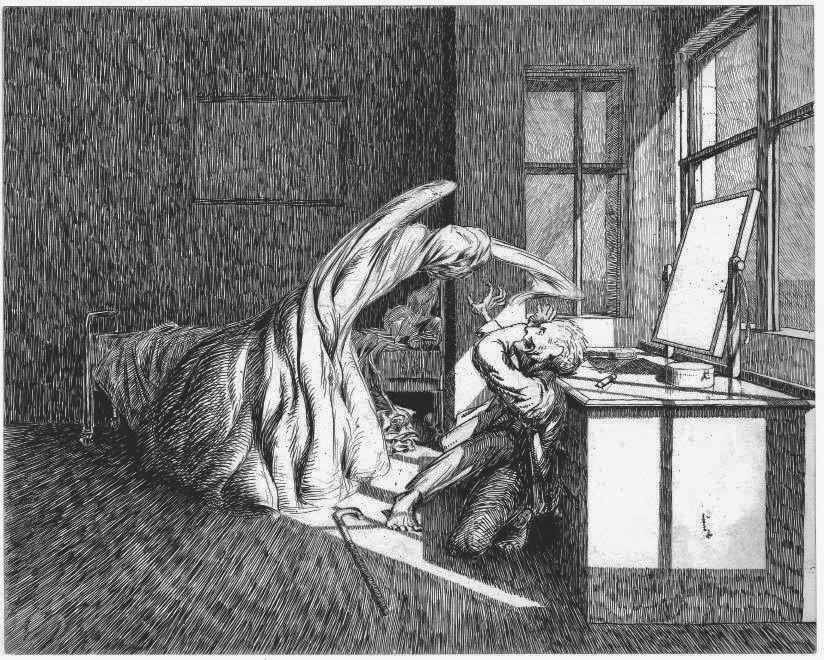

Illustration by James McBryde for MR James’s story “Oh, Whistle, And I’ll Come To You, My Lad”, first published “All Hallows Eve 1904”. As recounted in the book’s preface, James was close friends with the illustrator and its publication was intended as a showcase for the illustrator’s artwork. McBryde died having only completed four plates. If that’s not spooky…

This, to lapse into literary critical jargon for a moment, is the business. It’s got everything you want from a ghost story, and provided the template for much of James’s other ghost stories: an innocent professor of something arcane (Ontography, in “Whistle”’s case, whatever that is) who gets in over his head after discovering an ancient artefact of great malice, and an apparition of great power which is yet also indistinct.

It gives me the heebie-jeebies just to think about it. And if you want to spend the dark months of winter looking anxiously over your shoulder and wondering what that noise was, then I strongly suggest you get hold of a copy of Ghost Stories of an Antiquary right now. You won’t regret it. Or maybe you will.

Nicholas Lezard has been a freelance writer since God was a boy. He writes the Down and Out column for the New Statesman, and lives in Brighton.

Leave a comment