We Can Be Heroes: excerpt and interview with author, Paul Burston

|

Listen to this article

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Following the release of Paul Burston’s new book, We Can Be Heroes, we have an excerpt from his book, and an exclusive interview with the author…

Following the release of Paul Burston’s new book, We Can Be Heroes, we have an excerpt from his book, and an exclusive interview with the author…

Chapter 13: We Can Be Heroes

December 1, 1989. World AIDS Day. An unmarked white van is slowly snaking its way through Parliament Square towards Westminster Bridge. The driver is an ex-military man named Alan. Packed in the back are a dozen men and women, none of us from a military background, all of us personally embattled in one way or another.

…we padlock the chain to either side of the bridge, before handcuffing ourselves to it and tossing the keys into the Thames

Halfway across the bridge, the van suddenly stops. The rear doors fly open and we jump out, carrying a thick iron chain. Dodging the traffic, we padlock the chain to either side of the bridge, before handcuffing ourselves to it and tossing the keys into the Thames below. Some of us are holding bunches of flowers, the kind you might place on a loved one’s grave. We link arms as a show of solidarity and begin our protest. ‘Act up! Fight back! Fight AIDS!’

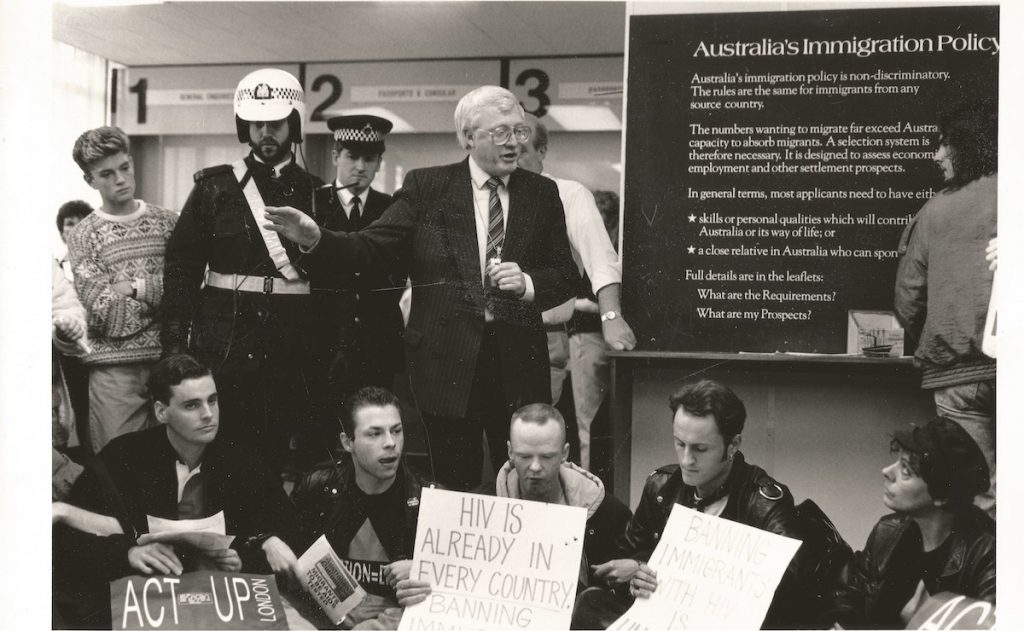

I joined ACT UP shortly after my friend Vaughan told me he was HIV+. By the time I was chaining myself to Westminster Bridge some ten months later, it had completely taken over my life. ACT UP stood for AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power. There was no formal structure or hierarchy, but rather a variety of subgroups dedicated to direct action, fundraising, media liaison, outreach and so on.

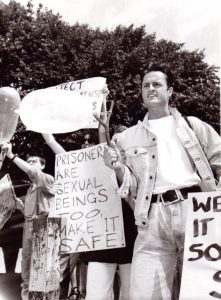

I volunteered to be part of the action group. Not everyone could afford to get arrested. Some had family to think about or jobs to protect. But everyone was equally welcome. Archive photographs from the time tend to show angry gay men in black leather biker jackets. There were certainly a fair few of those, myself included. But there were also a lot of women involved in ACT UP London – Stacy Baker, Ché Feenie, Emma Hindley, Jo Mackie and Maureen Oliver, to name just a few.

At that very first meeting I met a beautiful young biker boy called Spud Jones, who quickly became one of my closest friends. As I soon discovered, activism can be a powerful bonding agent. Spud was the singer in a band called Tongue Man, who released punky, noisy, unapologetically gay records with titles like Joys Of A Meatmaster. He was never destined to appear on Top Of The Pops.

But another member of ACT UP often did. Jimmy Somerville had been part of the soundtrack to my life from Smalltown Boy through to his recent hit, Don’t Leave Me This Way, the Communards’ cover of a disco classic, interpreted by many as a tribute to those recently lost to AIDS. His new solo single Read My Lips (Enough Is Enough) was a protest song calling for increased funding to tackle the pandemic.

The aim wasn’t simply to vent our anger but to raise awareness of the issues affecting people living with HIV and AIDS

ACT UP was committed to ‘non-violent direct action’, sometimes referred to as ‘civil disobedience’ – otherwise known as breaking the law. The aim wasn’t simply to vent our anger but to raise awareness of the issues affecting people living with HIV and AIDS, be they welfare cuts, discrimination in the workplace, homophobic reporting in the press, or the failure of prisons and other services to provide free condoms and needle exchanges to help stop the spread of the virus.

Demonstrations were referred to as ‘zaps’ and tended to be rather theatrical in nature. For example, ACT UP New York famously staged an enormous ‘die-in’ at St Patrick’s Cathedral and stormed the offices of politicians and drug companies, covering desks and computers with fake blood. ACT UP Paris lowered a giant pink condom over the Egyptian obelisk in the city centre.

ACT UP London. Photo: Gordon Rainsford

It’s fair to say that ACT UP London never reached such dizzy heights. Our first zap involved catapulting condoms over the walls of Pentonville Prison. When it became clear that rubbers wrapped in foil didn’t have the density required to scale prison walls, we inflated the condoms and tried to float them over instead. We also chained ourselves to the gates of Downing Street on the day the Chancellor of the Exchequer, John Major, was due to deliver the budget. As his car approached, a group of us leaped out and handcuffed ourselves to the gates, blocking his path. My photo appeared in one of the gay free sheets under the headline ‘Not budging on budget day’. Five people were arrested and referred to as ‘the ACT UP five’.

Another time, we invaded the offices of the Daily Mail, cunningly disguised as motorcycle couriers. The target of our protest was columnist George Gale, who peddled the kind of victim-blaming AIDS commentary typical of the period. I was sporting rather a luxurious quiff at the time and questioned whether a motorcycle helmet was really necessary as it might flatten my hair. My friend Emma rolled her eyes and reminded me that this was no time for vanity. Photographs taken inside the Daily Mail offices show Emma, Jimmy, me and others handcuffed to some railings while a security guard looks on perplexed. My hair looks suitably disarrayed but disappointingly lacking in volume.

But mainly we blocked traffic. As my fellow activist and soon-to-be boyfriend William often said, our battle cry could have been ‘ACT UP London, lie down!’ Joking aside, this was one way to guarantee media coverage. If all else failed, at least we’d make the traffic news.

So when the government announced benefit cuts to people living with HIV, AIDS and other life-threatening illnesses and chronic conditions, we staged a die-in next to the Cenotaph on Whitehall. A dozen of us lay across the road, clinging on to a large banner and chanting, ‘Living with AIDS, dying for money!’ I was one of the first to be dragged away by the police, who didn’t arrest me but simply dumped me on the pavement. I picked myself up and tried to re-join the protest, only people were packed so tightly together there was no room for me to squeeze in. I had to outrun the police and approach the demo from a different angle, lying back down in the road but facing the opposite way to everyone else.

The moment was captured by photographer Gordon Rainsford and remains one of my favourite ACT UP photos. I might look a right poser, but it’s a pose with purpose. My ‘Action = Life’ T-shirt is clearly visible. The look on my face is one of grim determination.

ACT UP die-in, London. Photo: Gordon Rainsford

Interview: Paul Burston

Author Paul Burston. Photo: Krystyna FitzGerald-Morris

Paul Burston wasn’t always the iconic voice of LGBTQ+ London that he is today. He grew up in a working-class community in a small town in South Wales – the product of an unhappy marriage and a broken home, a queer kid who was bullied from an early age, and a survivor of childhood abuse.

At 19, he moved to London and came out, hoping for a happier life, only to watch in horror as his new-found community was decimated by AIDS, fearing that he might be next. He survived.

Driven by grief and a powerful sense of survivor’s guilt, Paul joined ACT UP and became an AIDS activist. He was arrested, prosecuted, and developed coping strategies that would only increase his suffering and fuel his euphoria.

Read more: Polari, Britain’s secret gay language and its influence today

Having been born well after the AIDS pandemic and not having a great deal of knowledge about the times, we asked our youngest team members here, Ellie Mongey and Beth Pratt, to read up on this, put their heads together, and craft some questions for Paul…

Q: How did you feel when you were prosecuted and arrested for standing up for something you felt so passionately about?

P: “This was when I was charged following a protest with ACT UP. I was often arrested on demos, but this was the one time I was prosecuted, and the case went to court. I won’t pretend I wasn’t scared. But I also knew that I was right to protest against such bigotry and injustice, and I had the support of those closest to me – my fellow activists, including my cousin and flatmate Elaine.

“I also knew that I hadn’t actually broken the law on this occasion, certainly not at the time of my arrest. I was standing on the pavement, being interviewed by a reporter from the BBC! So I went into the courtroom putting on a brave face and hoping for the best. When I was found not guilty, it felt like a huge triumph. I left court feeling like a hero.”

Q: At what point in your life have you felt most liberated?

P: “I’ve felt liberated in different ways at different times. Coming out for the first time was hugely liberating. Joining ACT UP and finding an outlet for my grief and fears about AIDS was liberating. Recovering from drug and alcohol abuse was liberating. For me, liberation is all about being true to yourself. I’ve been true to myself in different ways at different times. But I think I’m the most authentic version of myself right now.”

Q: Looking back at your life so far, what has been your biggest achievement?

P: “Refusing to take ‘no’ for an answer. I’ve always been very driven and bloody minded when I felt it necessary. So whether it was demonstrating as an AIDS activist, writing magazine columns, newspaper articles and novels featuring gay characters, or creating a literary salon and book prize for other LGBTQ+ writers, it all feels like part of the same thing. It’s all about trying to make the world a better, more diverse and inclusive place.”

Q: Was it difficult to be so vulnerable and honest with your readers? Did that make the writing process tricky at all?

P: “Not really. I’ve always been very open, certainly since I came out when I was 19. As the years have gone by I’ve become more comfortable in my own skin, so deciding to write a memoir wasn’t that daunting. And there wouldn’t have been any point in writing it if I wasn’t completely honest. They say that honesty sets you free. Writing the book was certainly freeing, even when I was writing about mistakes I’ve made and moments I’m not proud of. There are many things I wish I’d done differently. I certainly have regrets. But they all led me to where I am now, so I try not to dwell on them too much.”

Q: Your work and life are so intertwined your work is your life, and your life is in your work. How do you rest, heal, and take a break from it all?

P: “With great difficulty! Ha ha! I live in my head a lot, so physical exercise helps. I enjoy working out, walking, swimming, and getting lost in a good book. Reading has always been a great source of escapism and sustenance for me. Books have saved me on so many occasions. I’m thankful that my mother always encouraged me to read. It’s been one of the greatest pleasures of my life.”

Q: Do you think more people should be sober?

P: “I think it depends on the person. I know lots of people who enjoy a glass of wine with dinner or can drink socially without it ever becoming a problem. Sadly I’m not one of those people. I can’t drink responsibly. I would drink to excess. So for me personally, sobriety makes more sense. But I wouldn’t judge anyone for drinking. It’s only if the drink becomes a problem that they might want to step back and think about it.”

Q: Do you agree that the best years of your life come later in life?

P: “I agree with what David Bowie said about ageing – it’s the process by which you become the person you were always meant to be. That’s assuming you have the luxury of ageing. So many people I knew didn’t have that luxury. So I’m very grateful that I do.”

ACT UP members in Australia. Photo: Gordon Rainsford

Q: Would you say that it is the resilience of community that gives you hope and inspiration during dark times?

P: “Absolutely. I’ve always taken inspiration from those around me, whether it’s people I’ve known personally, like Derek Jarman, or those I’ve only read about or seen from a distance. Community is hugely important to me. It’s what the author Armistead Maupin calls ‘logical family’ – which can include those you’re related to and those you’ve chosen. I can relate to that. My logical family means the world to me.”

We Can Be Heroes is available from Queer Lit for £8.29

Beth is one of Silver’s interns. She loves reading and studying literature. Entering her final year of university, Beth still finds time to dance, swim, and have a pint with friends. Her favourite hobby is going to coffee shops, if you can call it a hobby!

Leave a comment